John D. Rockefeller once said:

“The way to make money is to buy when blood is running in the streets.”

Warren Buffett echoed this statement when he said:

“Be fearful when others are greedy, and be greedy when others are fearful.”

What’s interesting about these two statements is that they address the emotional, rather than financial, aspect of investing. And as we’ll explore today, how we manage the emotional component of our investment decisions can make the difference between success and failure.

Few of us want to admit it, but as human beings, our emotions are often the biggest driver of our investment decisions. As such, they are also the biggest driver of our returns. Learning how to anticipate and control our emotions is one of the most important endeavors any investor can undertake.

The classical model of investing suggests that investors always make rational decisions, and invest with the goal of achieving the best risk-adjusted long-term returns. But research shows that investors invariably focus on the short-term, and consistently make decisions that are counterproductive to the goal of amassing long-term wealth.

The “Behavior Gap”

The root cause behind many of these poor decisions are the emotions that investors must confront and manage during their investment journey. Evidence from numerous studies on behavioral finance suggests that the need for emotional comfort costs the average investor around 2-3% per year in foregone investment return.

This shortfall, commonly referred to as the “behavior gap,” stems from the fact that optimal long-term financial decisions are often very uncomfortable to live with in the short-term.

Before you write off 2-3% as an unsubstantial amount, consider that an investor who earns a 7% return per year instead of a 4% return will have twice as much wealth after 25 years. For some, such as those who buy in near market tops or sell near market bottoms, the cost can be substantially higher.

With so much riding on our investment decisions, we owe it to ourselves to understand the emotions that occur at various phases of the market cycle. By identifying periods when we are likely to deviate from rational judgement, we can better equip ourselves to handle the short-term pain that’s required to achieve long-term gains.

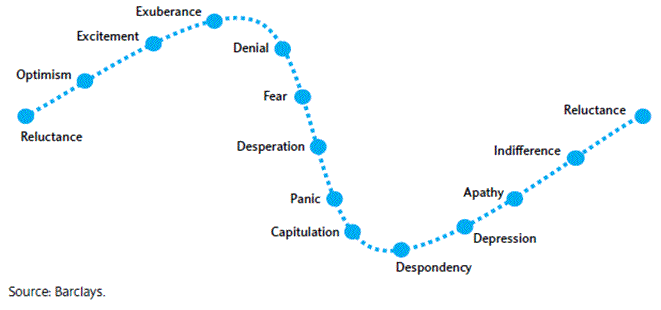

The Cycle of Emotions

The following chart is an approximation of the emotional states that accompany a typical market cycle. You can think of the dashed line as representing asset prices through an economic expansion and ensuing recession.

Reluctance

The best place to begin our journey is at the Reluctance stage. This is because reluctance tends to be the default state for most investors.

Under normal circumstances, our fear of taking risks and being wrong outweighs our fear of missing out. In behavioral finance, this is referred to as loss aversion, and describes the tendency of individuals to strongly prefer avoiding losses to acquiring gains. Said differently, losing $1,000 hurts more than winning $1,000 feels good.

This bias, in which “losses loom larger than gains,” has interesting implications for investors. It suggests that by default, we are all risk-averse individuals. While this can be beneficial from a survival perspective, it works against us when it comes to investing.

One of the primary manifestations of loss aversion is failing to invest completely (leaving cash on the sidelines or in risk-free, low-interest-bearing investments). While it provides comfort in that we can’t lose what we don’t invest, what we are really doing is purchasing short-term emotional comfort at the cost of long-term returns.

Optimism to Exuberance

As financial markets rise and the economy continues to expand, our natural state of reluctance slowly begins to diminish. As nearly anyone can attest to, repeated news stories showcasing new highs in the market and water-cooler conversations about how our friends and colleagues are making gobs of money can easily change our emotional state.

At this point our fear of failure quickly morphs into a fear of missing out. Pay special attention to this particular shift whenever you recognize it, because it is one of the most disastrous mindsets an investor can have.

It is during these stages of Optimism, Excitement and Exuberance that our natural aversion to loss now pushes many investors into the market. We start to view “losses” as missed opportunities rather than actual losses, and entering the market now acts to increase short-term emotional comfort.

Entering the market during these stages feels comfortable because we’re running with the herd, not against it. And typically by this point we’ve also entered a sustained period of positive results, which helps to blur our perception of risk.

But unfortunately, by the time most investors are optimistic and excited about the markets, most of the gains have already been made. By waiting for short-term assurance that the markets are safe to invest in, these investors are actually harming their long-term returns by buying once prices are already high.

Investors who enter the market during the Excitement and Exuberance phases typically see only marginal gains before the cycle ends, and prices begin to roll over.

Denial to Panic

The funny thing about market tops is that when they’re occurring, no one knows for certain whether it’s an actual top. Positive emotions have a tendency to carry on long after a market has reached its peak, and as a result, investors begin to shield themselves (psychologically) from negative news. They move into the Denial phase.

The reluctance to sell that we see during the denial phase has the effect of keeping the markets artificially high for a while, as conditions begin to deteriorate. Savvy investors who are able to set their emotions aside and look at financial conditions objectively will begin to reduce their holdings at this stage, but for most investors, the feeling of denial is just too strong.

They can’t believe that the party’s over, and they don’t see the writing on the wall. As the markets continue to decline, they move from Fear to Desperation, and finally to Panic.

As prices fall, loss aversion again acts to influence poor decision making. Wanting to avoid the emotional pain of taking a loss (even a small one), investors have a tendency to hold on to their losing investments instead of cutting them loose.

This is because as the value of our portfolio falls, the pain of selling at a loss increases, but at a diminishing rate. The first 5% loss hurts the most. But once you’ve already lost 25%, the difference between losing 25% and 30% often becomes negligible. Our emotions are once again hard at work distorting our perception of risk and reward.

Capitulation to Reluctance

Eventually, as losses continue to build, many investors will reach a point of Capitulation. They finally say, “enough is enough” and exit the market.

In some cases, investors reach this tipping point by force. A lack of financial liquidity can create a situation where investments must be sold to cover expenses. But more often than not, investors sell at this point because they’re scared, stressed, and need the security of having their money in cash.

In effect, they’ve depleted their reserve of emotional strength. They no longer have the resilience required to deal with the stress and anxiety of staying invested.

This is perhaps the most dangerous place an investor can find themselves in. Not only have they effectively locked in their losses, the emotional roller coaster they just endured is likely to leave long-lasting scars.

Many of those who capitulate near the bottom swear off investing altogether. They decide that investing isn’t for them, and resign themselves to the safety of cash.

Once you’ve exited the market for emotional reasons, it’s very difficult to get back in. As the chart above shows, an investor must move through the stages of Despondency, Depression, Apathy and Indifference, just to get back to the Reluctance stage. This can take years, and during the process many of these investors miss out on substantial gains as the market recovers.

Using the Cycle of Investor Emotions to Your Advantage

For most of us (sociopaths excluded) turning off the emotions we feel when investing is impossible. After all, our financial livelihood is on the line, so it’s bound to affect how we feel. The trick, however, comes in distancing ourselves from our own emotions, while zeroing in on the emotional states of other investors.

In terms of our own emotions, we must learn how to be comfortable being uncomfortable. That is, we must realize and wholeheartedly accept that what our emotions are telling us to do at any given point is most likely wrong. Whenever we feel optimistic or excited about investing, chances are that the market is nearing a peak, and we should exercise caution. And when we’re in a state of desperation or panic, wanting nothing more than to sell our holdings, there’s a good chance we should be doing the exact opposite.

Understanding that your emotions will reliably tell you what NOT to do is the first step in overcoming their influence on your portfolio.

The other way to profit from understanding the cycle of investor emotions is simply to use it as a guide for assessing where we are in the market cycle. When everyone’s constantly talking about how much money they’ve made in stocks (Excitement and Exuberance), it’s a good indication that valuations are rich and perhaps money should be taken off the table. Conversely, when the economy and markets are in a state of despair and panic, know that the good times are about to begin and get ready to take advantage.

There is one last way to capitalize on the emotional nature of the financial markets, and that’s by following our investment models. By using a rules-based approach to investing, you can remove the emotional component of your investment decisions entirely. This is the quickest and easiest way to say goodbye to the “behavior gap” that may be limiting your returns.

An innovative approach for eaming higher returns with less risk

Download Report (1.2M PDF)You don’t want to look back and know you could’ve done better.

See Pricing