These days, the rage is all about passive investing. That’s because over the last few decades, it’s become crystal clear that active management (aka. stock picking) doesn’t work. Even the most astute stock pickers, with millions of dollars’ worth of research at their fingertips, consistently underperform basic index funds.

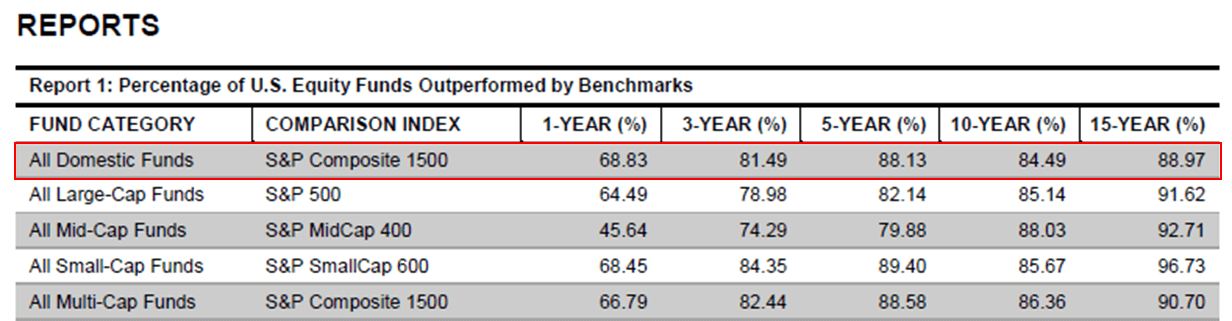

We’ve discussed this enigma before, but if you need more proof, take a look at the Standard and Poor’s Active Vs. Passive Scorecard (SPIVA). You’ll notice that over the last 15 years, 88.97% of domestic active management funds have underperformed their benchmark.

In other words, 9 out of every 10 actively managed funds has charged hefty fees in order to deliver worse returns than one could get from a simple index fund. (If you’re still paying for active management, give us a call … we have a bridge to sell you.)

As more investors have come to realize this, we’ve seen an exodus from actively managed funds. But as investors have fled these funds, they’ve unknowingly jumped from the frying pan into the fire. Little did these investors realize that managing their own portfolios requires the avoidance of numerous psychological pitfalls, most of which the average investor has never come face to face with.

The Sad But True Performance Statistics

Every year, a firm called Dalbar puts together a highly informative report known as the Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior (QAIB). This report measures the effects of investor decisions to buy, sell and switch into and out of mutual funds over various timeframes. The goal is to understand whether or not individual investors earn the same returns as the funds they invest in.

Naturally, you’re probably thinking to yourself, “Of course they earn the same returns, they were invested in the fund, right?” Well, not so fast. As we’ll see, individual investors have a habit moving into and out of these funds at inopportune times. The net result is that actual investor performance drastically underperforms that of the funds themselves.

Consider the following performance data from Dalbar’s 2018 Quantitative Analysis of Investor Returns. This table provides index returns and average investor returns across four different time periods.

| Individual Investor Performance vs. Index Funds | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time Period | Average Stock Investor Return | S&P 500 Index Return | Performance Gap | Effect on Growth of a 100K Portfolio | ||||

| 20-Year | 5.29% | 7.20% | -1.91% | -$121,317 | ||||

| 10-Year | 4.88% | 8.50% | -3.62% | -$65,061 | ||||

| 5-Year | 10.93% | 15.79% | -4.86% | -$40,165 | ||||

| 3-Year | 8.12% | 11.41% | -3.29% | -$11,893 | ||||

| Data from Dalbar’s 2018 Quantitative Analysis of Investor Returns | ||||||||

Notice that regardless of which time period we look at, actual returns to investors are significantly below the corresponding index returns. This performance gap leads to staggering differences in one’s portfolio over time, as we can see in the right hand column (keep in mind that these figures rise in proportion to the size of one’s portfolio).

So why is this? Why does the average stock investor underperform the market so consistently? The answer is going to surprise you … it’s because we’re hardwired to make irrational decisions when it comes to money.

An Introduction to Your Behavioral Biases

Let’s begin with a brief thought experiment. Those who have read our special report may have seen this before, but this example, provided by Daniel Kahneman – a Nobel Prize winning researcher and pioneer in the field of behavioral finance, does a great job introducing you to your mind’s own fallacies.

As you consider the next question, please assume that Steve was selected at random from a representative sample.

An individual has been described by a neighbor as follows: “Steve is very shy and withdrawn, invariably helpful but with little interest in people or in the world of reality. A meek and tidy soul, he has a need for order and structure, and a passion for detail.”

Is Steve more likely to be a librarian or a farmer?

Well, what did you choose? If you said “librarian,” congratulations, your portfolio just lost 10% of its value.

The resemblance of Steve’s description to a librarian is obvious, but did you stop to consider what other information might be relevant? As Kahneman asks, did it occur to you that there are more than 20 male farmers for each male librarian in the U.S.?

The point here isn’t that you failed to recognize that there are many more male farmers than librarians, it’s that most likely – you didn’t even think to ask.

When individual investors make their own portfolio decisions, a similar dynamic is at play. Important investment decisions are often made based on a limited amount of information at hand, without taking into account other equally (or perhaps more) relevant information.

This phenomenon is known in the world of behavioral finance as the availability heuristic. It’s one of over a hundred so called “behavioral biases” that are hidden deep in your mind, distorting both your perception and your ability to make sound decisions.

The 5 Most Dangerous Behavioral Biases

Of all the potential psychological pitfalls out there, a few have earned their place at the top. We’re going to briefly discuss the top five behavioral biases so you can understand the extent to which your mind is working against you.

Loss Aversion – This bias reflects the well documented phenomenon that losses trigger a much stronger psychological reaction than an equivalent gain. Said differently, losing $1,000 hurts more than winning $1,000 feels good. Some studies suggest that losses are actually twice as powerful, psychologically. Why does this matter? Because it induces poor investor behavior such as investing only in low-risk, low-return investments, and hanging on to losing positions far too long. These are two of the worst mistakes an investor can make.

Anchoring – This refers to the tendency to rely too heavily on one piece of information when making decisions. For example, once you’ve made an investment, it’s common to view the success or failure of that investment in relation to the original purchase price, which becomes the “anchor.” That, by itself, is fine, but the problem arises when it comes time to sell. Most investors will base their decision at least in part on whether they have a gain or loss. The original purchase price is acting as an “anchor” in their mind, affecting their decision. If you think about this logically, what you paid for something has absolutely no relevance regarding whether you should continue to hold or sell the position. All that matters is the future outlook for that particular investment.

Herding – This one probably doesn’t need much explanation. Herding simply refers to our natural tendency to feel safe and secure when we’re in sync with the crowd. Back during our early history, this survival instinct helped us avoid being ostracized from our tribe, which often meant death. But these days, it actually facilitates events such as stock market bubbles and market crashes. Our natural inclination to do what the crowd does leads us to chase markets as they go higher, and flee them as they collapse – both of which are detrimental to overall performance.

Confirmation Bias – Do you carefully gather and evaluate facts and data before reaching a conclusion? Probably not. If you’re like most, you tend to reach a conclusion first, then seek out information that supports your preconceived notions. Ever wonder why it’s so hard to change someone’s mind? It’s because once they’ve decided on a particular belief, the mind instantly goes to work searching for validating information, while ignoring (or distorting) the rest. Think the stock market’s going down this year? I bet you can find a whole lot of evidence to support your claim.

Overconfidence – This one’s a biggie. Also called illusory superiority, this phenomenon is where people overestimate their own qualities and abilities in relation to others. Ask a group of people if they’re above average drivers, and the vast majority will say yes. Ask them if they’re better looking than average, and the vast majority will again, say yes. The same is true with investing. You probably think you’re much better than you really are, when in reality that might not be the case. This is particularly true if you don’t work in the investment industry.

It’s Not Just You

We could go on, but hopefully by now the point is clear. Besides being at a severe informational disadvantage, investors trying to manage their own portfolios have the cards stacked against them. Your own mind is literally working against you.

But here’s the funny part, it’s not just regular folks like you that are affected by these decision making pitfalls, professional money managers are just as susceptible. They’re human, just like us, and are subject to the exact same biases. We started this article off by demonstrating that even they, as a group, habitually underperform the indexes. You should now have a solid understanding of exactly why that is.

So where does that leave us? If you’re not mentally equipped to manage your own portfolio, and even those who pick stocks for a living can’t beat the indexes, what’s an investor to do? The answer is twofold.

First, as we always recommend, avoid managed funds and their high expense ratios and invest solely in ETFs and index funds. Since it’s highly unlikely that you will outperform the indexes by trading in and out on your own, just sit tight and minimize overtrading.

For most investors, those simple actions alone are enough to eliminate the performance gap that we looked at in the table above. However, those looking to further enhance their returns have one final alternative that we’d like to mention.

Recognizing that all subjective human decisions are subject to a whole host of behavioral biases, and that the performance of various investments is a function of where we are in the economic cycle, a handful of investment firms have transitioned to what’s known as algorithmic portfolio management.

This process involves removing the human component from the decision making process entirely, and instead leveraging key data across the economy and financial markets to make allocation decisions. Our investment models are a perfect example of this approach, and we’re proud to be at the forefront of this shift in investment philosophy.

If you’ve experienced subpar performance in the past, take a moment to see what following our investment models can do for your portfolio. In just a few short minutes you can be following a proven strategy that solves the two biggest problems individual investors face: avoiding behavioral biases, and being at an informational disadvantage.

An innovative approach for eaming higher returns with less risk

Download Report (1.2M PDF)You don’t want to look back and know you could’ve done better.

See Pricing